Does putting ice in a swamp cooler make sense? Hardly.

It definitely skyrockets your swamp cooler running costs.

Quick answer: Putting ice in a swamp cooler doesn’t make sense. The addition of ice doesn’t significantly enhance cooling, it increases energy consumption and cost, and ice melts rapidly in the cooler’s environment. Moreover, the design of many swamp coolers prevents the inclusion of ice in the tank.

How does a swamp cooler work? Does it need ice?

A swamp cooler cools down air by evaporating water. Water evaporation sucks heat energy away from the air.

A water pump takes the water from the cooler’s tank and distributes it onto a cooling pad.

A fan then propels air through this water-saturated pad. As the water evaporates, it absorbs heat from the air, effectively cooling it down.

Now, this whole process operates under a particular premise: the pump is designed to transport liquid water, not solid ice.

If you’re considering adding ice, it must be in a water-ice mix form

This ensures that the pump can effectively transport the mixture onto the cooling pad.

Can ice in the tank affect water evaporation?

The thought of adding ice to a swamp cooler may seem sensible at first glance.

Ice is colder than water, so it should increase the cooling power, right?

Unfortunately, it’s not that straightforward.

Remember, the cooling effect is primarily generated at the water pads where the evaporation occurs.

These pads, by design, always remain above the melting temperature of ice because their purpose is to facilitate the evaporation of liquid water.

Consequently, even if ice is present in the tank, the water pads’ temperature is unlikely to decrease significantly.

This suggests that the presence of ice might not yield a noticeable increase in the cooler’s performance.

Does ice in a swamp cooler increase running costs?

Understanding the financial implication of freezing water into ice is critical to determine if it’s cost-effective to add ice to your swamp cooler.

How much does freezing water to ice cost?

The process of freezing this water requires two main steps. First, the water needs to be cooled from room temperature (about 20°C) to 0°C (freezing point).

The energy required for this can be calculated using the formula Q = mcΔT, which gives us approximately 83,720 joules to freeze one kg of water.

For anyone interested: The formula Q = mcΔT is used to calculate the amount of heat energy (Q) required to change the temperature (ΔT) of a given mass (m) of a substance with a specific heat capacity (c). The heat capacity of water is 4.186 J/g°C.

Next, to convert the cooled water to ice, we need an additional 334,000 joules.

To get this number you can use the formula Q = mL, where ‘L’ is the latent heat of fusion for water (334 J/g).

So, to freeze a kilogram of water, you need

Energy = Heat extraction energy + Heat fusion energy = 83,720 joules + 334,000 joules = 417,720 joules

1 US gallon is 3.785 liters of water, so:

In total, to freeze 1 gallon of water your freezer would need to do about 1.581 Megajoules of work.

( 1 Megajoule = 1,000,000 Joules = 1,000,000 Ws (Watt-seconds) = 277.77 Wh (Watt-hours) ≈ 0.278 kWh (Kilowatt-hours) )

In total, your freezer would need to do about 7.9 million joules (or 7.9 megajoules) of work to freeze 5 gallons of water from room temperature down to the freezing point.

That would be half a swamp cooler tank’s worth of ice.

With an average electricity cost of 23 cents per kilowatt-hour in the US currently, and considering that one kilowatt-hour equals 3.6 megajoules, it costs approximately 50.4 cents to freeze 5 gallons of water.

Does filling ice in a swamp cooler increase overall running costs?

Yes, adding ice to your swamp cooler not only incurs the cost of freezing water but also impacts the overall energy efficiency of the cooler.

A 10-gallon swamp cooler tank lasts you 4 hours. During these 4 hours, a regular 250W swamp cooler uses 1 kWh of energy, and this consumption doesn’t change when ice is added.

However, the energy expended to freeze the water into ice significantly increases the overall energy usage.

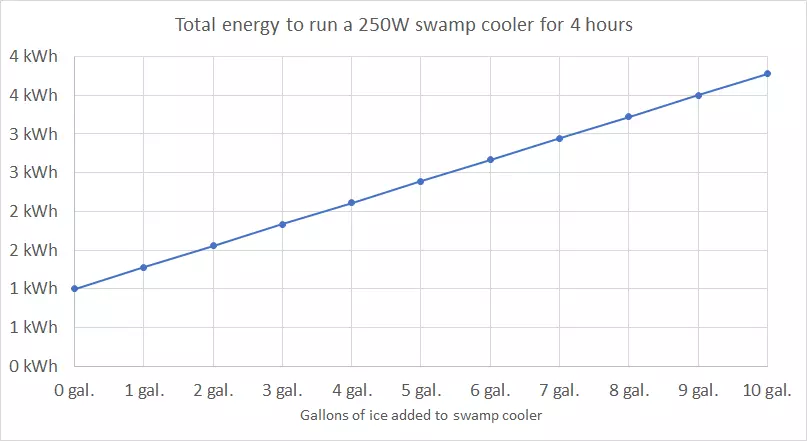

I calculated how much electricity a swamp cooler consumes when you run it for 4 hours.

Here’s the result in a table:

| Ice Added to Tank (gallons) | Total Energy Expenditure (kWh) | Total Cost per Swamp Cooler-Hour |

|---|---|---|

| 0 gal. | 1 kWh | $0.23 |

| 1 gal. | 1.28 kWh | $0.29 |

| 2 gal. | 1.56 kWh | $0.36 |

| 3 gal. | 1.83 kWh | $0.42 |

| 4 gal. | 2.11 kWh | $0.49 |

| 5 gal. | 2.39 kWh | $0.56 |

| 6 gal. | 2.67 kWh | $0.62 |

| 7 gal. | 2.95 kWh | $0.69 |

| 8 gal. | 3.22 kWh | $0.75 |

| 9 gal. | 3.50 kWh | $0.81 |

| 10 gal. | 3.78 kWh | $0.87 |

As you can see, the total energy and your total electricity cost increases the more ice you add.

For instance, with 5 gallons of ice, the total energy requirement becomes 2.39 kWh, and the running cost is now 55 cents, compared to 23 cents without ice. With 10 gallons of ice, it’s 3.78 kWh, and the running cost is 87 cents.

And please note: This calculation is assumes physically ideal circumstances. The energy cost does not factor in inefficiencies by your fridge, which might only be 50% or 80% energy efficient.

So, in practice, the cost is even higher than that!

As you can see, total energy consumption rises the more water you freeze for your swamp cooler.

As you can see, total energy consumption rises the more water you freeze for your swamp cooler.

Can you even put ice in a Swamp Cooler?

Interestingly, the question of adding ice to a swamp cooler isn’t merely about physics and finances.

The design of many swamp coolers presents a practical barrier to this idea. Several models come with a grid covering the tank opening, which prevents large objects, including ice, from being filled in the tank.

I am not sure if the manufacturers really created the grid in order to prevent you from filling ice in the tank. It might as well be to prevent other large stuff from entering the tank.

Hence, even if you want to add ice, the design of your cooler might not allow it.

Does an ice-filled Swamp Cooler or Portable Air Conditioner cost more to run?

When considering cooling options for your space, the comparison between a swamp cooler and a portable air conditioner often comes up.

My favorite portable AC is the Whynter ARC-14S since it is a dual-hose system and very efficient.

Let’s do a case study.

Unlike a swamp cooler, a portable AC works efficiently regardless of the climate. And just like a portable swamp cooler, you can easily move it to cool different rooms.

But how does it fare in terms of energy consumption compared to an ice-filled swamp cooler?

The Whynter ARC-14S has a cooling power of 14,000 BTU (British Thermal Units), and its Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER) is 11.2. This means that for every watt of power it consumes, it produces 11.2 BTUs of cooling. Given that 1 BTU is equivalent to 0.2931 watts, the Whynter ARC-14S consumes around 1.29 kilowatts of electricity.

Comparing this with our previous calculations for an ice-filled swamp cooler, we find that a 10-gallon cooler with 10 gallons of ice uses around 3.78 kWh over 4 hours or approximately 0.945 kWh per hour.

This suggests that even under the most extreme condition (the swamp cooler is completely filled with ice), the ice-filled swamp cooler still consumes less energy than the Whynter ARC-14S air conditioner.

So, surprisingly: If you feel like the ice in your swamp cooler helps you cool your room down, freezing water and putting it in a swamp cooler is still cheaper than running a portable AC.

Does an ice-filled swamp cooler or a portable air conditioner make more sense?

Despite the higher energy consumption, a portable air conditioner like the Whynter ARC-14S could still be a more sensible choice for some situations.

The effectiveness of a swamp cooler is heavily dependent on the climate. In humid conditions, their cooling power drastically decreases. On the other hand, an air conditioner performs consistently, regardless of the outside weather.

A portable AC is likely able to keep your room temperature consistently low whenever you want.

A swamp cooler filled with ice needs constant ice refills. Are you even able to produce that much ice around the clock?

If freezing water and refilling the water tank costs you 30 minutes of your time every day, and you assume an average wage of $15, that’s $7.5 worth of your time. So:

If you factor in physical effort, a portable air conditioner is way cheaper than an ice-filled swamp cooler.

Additionally, the process of freezing water to add to the swamp cooler, along with the quickly diminishing effects of the ice, introduces inefficiencies that aren’t present with a portable air conditioner.

While the upfront cost and energy consumption of a portable air conditioner might be higher, its efficiency, convenience, and versatility often outweigh these costs, particularly in warmer, more humid climates.

Remember, the best choice depends on your specific needs, budget, and environmental conditions. Consider all these factors before making your decision.

Conclusion

Given the underlying physics, increased costs, and potential design limitations, adding ice to a swamp cooler does not make sense.

It neither significantly enhances the cooling effect nor proves cost-effective.

To ensure effective cooling, focus more on regular maintenance of your swamp cooler. Changing the water regularly, cleaning the pads, and ensuring a constant supply of fresh air can all contribute to efficient operation.

If cooling is still insufficient, consider upgrading to a model with a higher cooling capacity or exploring alternative cooling systems like air conditioners. They might offer more cooling potential, though they are more energy-intensive.

Understanding the workings of your cooling system can help you make smart and informed decisions. Remember, effective cooling isn’t just about making things colder; it’s also about efficient and smart use of resources.